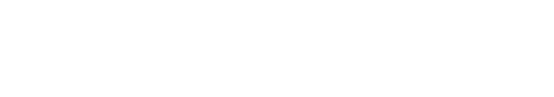

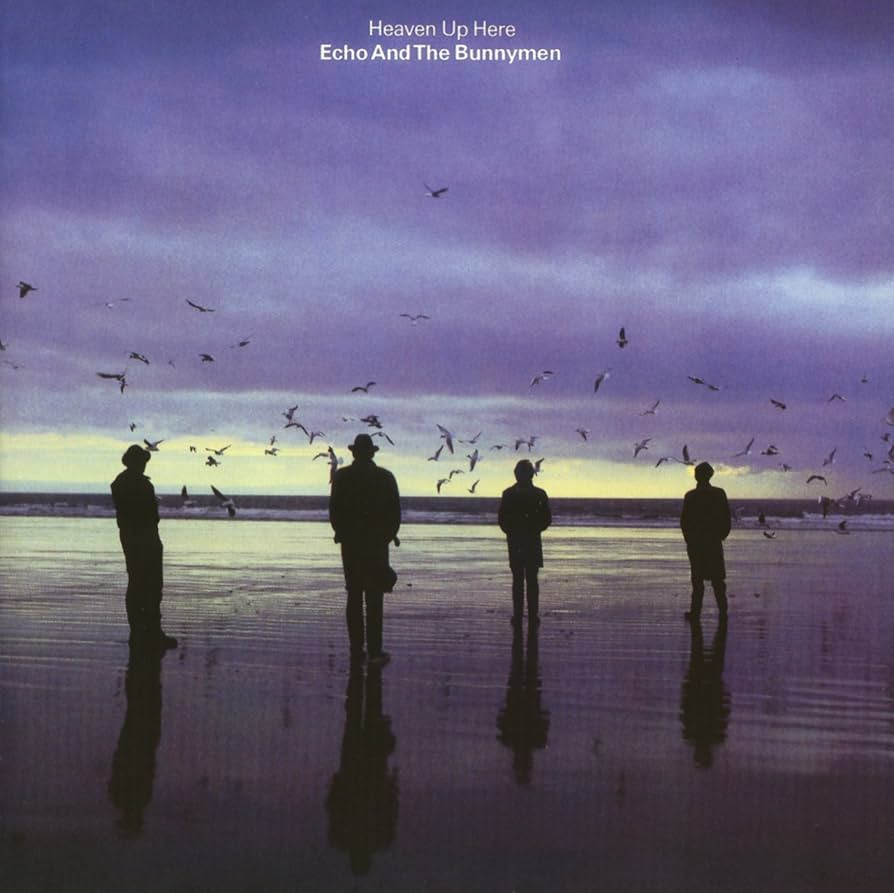

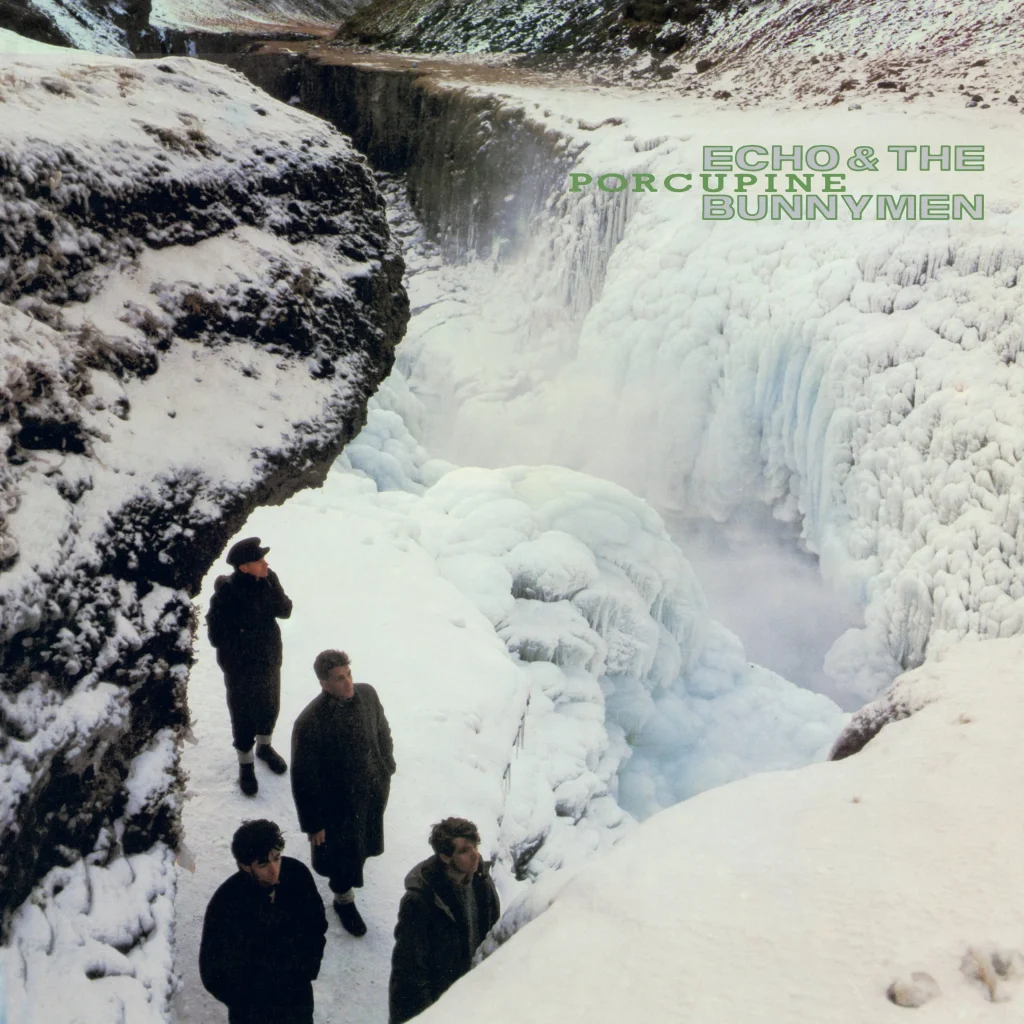

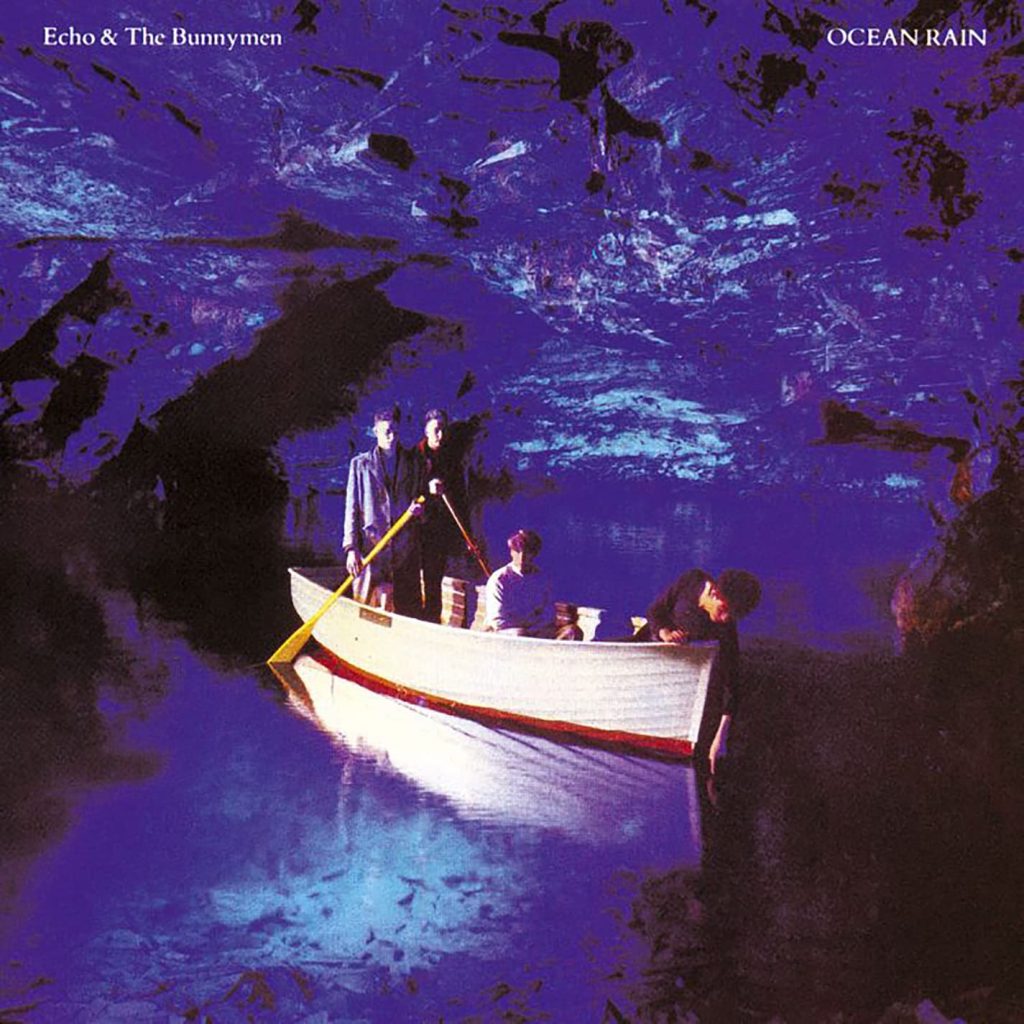

From the earliest days of Echo & the Bunnymen, Will Sergeant approached instruments, effects, and amps as “tools.” Roland drum machines, Jazz Chorus amps, Space Echo and Chorus Echo units, along with a host of BOSS effects, were the artistic mediums that gave voice to his self-directed musical vision. Sergeant’s inventive playing style—as heard on classic albums such as Crocodiles, Heaven Up Here, Porcupine, and Ocean Rain—flowed between taut melody, serrated rhythm, and shadowy psychedelia, forging a sound all his own. Celebrated for an enduring body of work and a band that continues to draw crowds, he has crafted unforgettable music that balances innovative technique with evocative songwriting. Post-punk icon? He’d likely shrug that off. Yet his story remains essential. It’s a glimpse into the creative mind of one of the guitar world’s greatest.

Post-Punk Icon

Renowned as a guitarist and key songwriter in Echo & the Bunnymen since their 1978 inception, Will Sergeant is a touchstone for generations of players. Emerging from the glamour and grime of Liverpool’s fertile underground scene, the legendary outfit formed a distinctive musical identity where propulsive urgency meets widescreen atmosphere.

Often dark, at times anthemic, and always steeped in poetic intensity, Echo & the Bunnymen’s sonic image pulsed with a fevered nocturnal energy. Sergeant, however, stops short of the goth moniker: “We were dark, and on the edge of goth, but there was no nonsense—no bats.”

“We were dark, and on the edge of goth, but there was no nonsense—no bats.”

Inspired Ingenuity

A leading figure in England’s post-punk movement and its evolution, the guitarist wielded Roland and BOSS gear with inspired ingenuity. These devices became extensions of his imagination, and he coaxed sounds no one expected to reveal a mind that hears in shapes and colors—both chiseled and painterly.

Along this creative path, Sergeant delved deeply into experimentation, pursuing boundary-pushing performance, studio innovation, and striking visual art with relentless curiosity. His recorded legacy proves that adventurous, left-field music-making and chart success are not mutually exclusive.

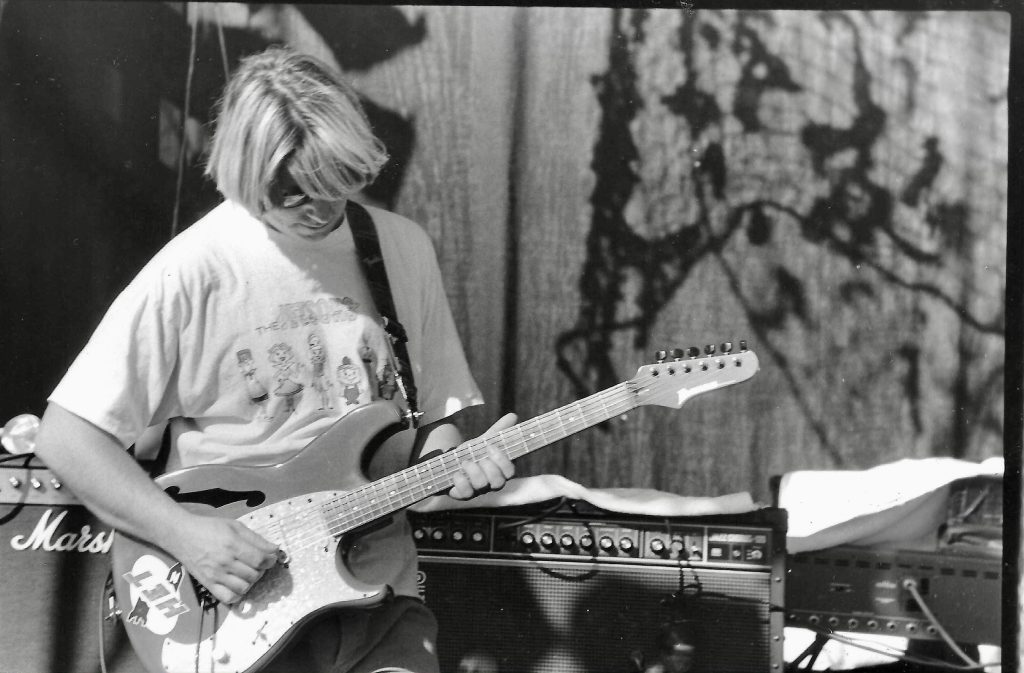

Following the release of their landmark 1980 debut album, Crocodiles, Echo & the Bunnymen went on to deliver a string of top-ten LPs that helped define the decade’s sound. At the same time, hit singles such as “The Cutter” and “The Killing Moon” aided their rise to international acclaim.

Prolific Collaborator

With a broad discography that includes several solo albums, Sergeant is also a prolific collaborator. His catalog spans numerous lesser-known projects, including Echo & the Bunnymen offshoots Electrafixion and Poltergeist, as well as the ambient electronic venture Glide.

More recently, Sergeant’s unmistakable guitar work elevated longtime friend Courtney Love’s latest album, lending texture and depth to a set of fiercely crafted alt-rock tracks.

BOSS caught up with the Bunnyman at his home near Liverpool—the World Capital City of Pop—to deep-dive on his favorite guitar gear and the art of crafting timeless tracks. Read on for rare insight and candid tales from across Echo & the Bunnymen’s long and storied history.

Spacetime

What were your go-to BOSS pedals and echo units in the early days?

My first BOSS pedal was a delay. That’s what I was all about: delay pedals and tape echo. That was the thing I liked the best. I loved making spacey noises using the time and feedback controls. I did that a lot with BOSS delay pedals and the Roland Space Echo and Chorus Echo tape delay units.

In the mid-’80s, I had a BOSS BCB-6 Carrying Box full of BOSS pedals: a DM-3 Delay, CE-3 Chorus, HM-2 Heavy Metal, CS-3 Compression Sustainer, and PSM-5 Power Supply & Master Switch. I remember the DD-3 Digital Delay coming out, too. I also had a volume pedal.

Back in the day, I used a Roland SRE-555 Chorus Echo. Years ago, I stupidly swapped it for something with Mark “Spike” Stent, the producer. Now, I’m thinking, “Why did I do that?” With the old Chorus Echo, I used to like adjusting the tape speed on the fly—getting it to slow down and speed up so the repeats changed pitch.

That was great. I’d do that live on “Do It Clean” to get a trippy sound and make weird noises. I like the sound of stretched tape, and that weird, fluttery thing you get—wow and flutter.

Control Tower

How did your guitar rig develop over time?

Eventually, all my BOSS pedals were built into a single system designed by Pete Cornish. He took all the innards from the original cases and put them in one box. That was linked to a custom-made pedal switcher board by a thick multi-cable.

The Pete Cornish unit was then put into a rig that we called the Tower. It was massive. It was a big flight case that also contained my Roland Jazz Chorus amp and Chorus Echo unit. If you watch the 1983 Rockpalast show, you can see it in the background.

"In the mid-'80s, I had a BOSS BCB-6 Carrying Box full of BOSS pedals."

Michael “Curly” Jobson (brother of Richard Jobson from the punk band Skids) was my roadie at the time. He went on to help get Lollapalooza going with Perry Farrell and some other people, including a bloke called Ted Gardner, who was our tour manager. The Pete Cornish unit was really my first step towards multi-effects. BOSS multi-effects didn’t exist at the time.

Multitasking

What drew you to BOSS multi-effects?

I always wanted a single switch that could turn multiple things on or off simultaneously. It was always a pain in the arse trying to switch two or three pedals at once. That’s the thing about multi-effects: you only need to press one switch, and you can change several effects, as opposed to jumping around like an octopus.

They sound great, and they’re dead reliable. People get snooty about them being digital. But get with it, daddy-o!

"I currently use the BOSS GT-100 [COSM Amp Effects Processor], which is old now, but it’s brilliant. It’s never let me down."

I currently use the BOSS GT-100 [COSM Amp Effects Processor], which is old now, but it’s brilliant. It’s never let me down. I have a couple of them. My tech, Davo [Andrew Davitt], and I back up the settings on a computer. We’ve got a spare in the lockup with the same sounds programmed in.

Set Design

How do you configure the GT-100 for your live workflow?

I’ve usually got about four different sounds programmed per song. The presets are labeled with the song title and parts, like “Killing Moon Mid” and “Killing Moon Outro.”

Me and Davo work out the presets using the [BOSS Tone Studio] software on a computer because it’s much more comfortable than crouching down on the floor. You can change the order of effects, and it’s easy to move presets around—which is great for making setlist changes.

The brilliant thing is that the presets are all in the order of the set. So, the first patches are always for the song “Going Up” because that’s what we normally start with. “Ocean Rain” is normally the last one. Patches for songs that we don’t play often are saved further up—number thirty-something or whatever.

"I’ve usually got about four different sounds programmed per song. The presets are all in the order of the set."

Patchwork

Could you give some examples of GT-100 effects you rely on in certain songs?

I use Slicer for a tremolo effect on “Bring on the Dancing Horses,” Rotary for a watery sound on “Seven Seas,” Chorus on “Never Stop,” Octave and Uni-V for an L. Shankar-style tone on “The Cutter,” stereo Pan for the ending solo on “The Killing Moon, and Slow Gear for the cello sound on “Ocean Rain.”

I like the tuner, and the expression pedal is good too. You can assign it to control wah or pitch. I also use it for volume quite a lot—for fading in and taking the attack off.

I don’t use wah on Bunnymen records much at all, but I do use it live. I go crazy on it—moving it dead fast to make the guitar sound like it’s underwater. You can hear that on a song we do called “Sister Pain” [from Electrafixion’s Burned album].

Which other BOSS multi-effects units have you used?

I’ve got a BOSS ME-10 [Guitar Multiple Effects] and a BOSS GT-10 [Guitar Effects Processor]. The GT-10’s Reverse effect is great. I used a BOSS ME-8 [Guitar Multiple Effects] before the ME-10, and a GT-8 [Guitar Effects Processor] before the GT-10. I’ve got a load of other BOSS stuff, including the RE-202 Space Echo, RC-600 Loop Station, a CS-3 Compression Sustainer, an SD-1 Super Overdrive, and various other distortion pedals.

All That Jazz

When did Roland Jazz Chorus amps become part of your setup?

I used Roland Jazz Chorus amps from the early ’80s. I used to use two at one point. Mac [Echo & the Bunnymen vocalist/guitarist Ian McCulloch] had one as well. I’ve still got a JC-120 somewhere.

At the time, everyone was going on about how dead reliable they were. They didn’t break and were great for travelling. They were very clean-sounding, but I also really liked the built-in distortion effect. I used it all the time on “All That Jazz.”

"I used Roland Jazz Chorus amps from the early '80s. The JC-120 effects are all really good: the distortion, reverb, chorus, and vibrato. I’ll have to dig my JC-120 out!"

The JC-120 chorus is cool too. I used it live at the beginning of “Rescue.” On the record [Crocodiles], the producer, Ian Broudie, got a chorus-style sound using a tape-machine trick he knew. I double-tracked my guitar bits, and he adjusted the varispeed to control the pitch.

I’ve been trying to recreate that sound using chorus effects ever since. The JC-120 effects are all really good: the distortion, reverb, chorus, and vibrato. I’ll have to dig my JC-120 out!

Space Odyssey

What kind of guitar gear were you using before discovering Roland and BOSS?

The first amplifier I had was a FAL (Futuristic Aids Limited) Merlin, and it had a great reverb sound. At the time, I didn’t know a great reverb from a shit reverb. I used to just turn it up full because it made things sound spacey and a bit like Hawkwind.

I had a Carlboro Flanger, but I never really used it much. I also had a Yamaha digital delay before I got a Roland RE-201 Space Echo. The Space Echo was great. I’d come across them in studios like Rockfield, and after hearing what they could do, I had to have one.

Once we started making some money, we bought the Roland SRE-555 Chorus Echo. It was similar to the Space Echo, but it was better for touring because it was rack-mounted. It had a sound-on-sound function I’d use to trip out on. I’d get crazy sounds using that. It’s brilliant. I’ve always liked experimenting with sounds.

"It was always about making the guitar sound not like a guitar."

Guitar Anti-Hero

How did your experimental approach to guitar playing emerge?

It was always about making the guitar sound not like a guitar. After punk, there was a rebellion against guitarists that could do all that fiddly-diddly, 500-notes-a-second stuff. It was a perfect time for someone like me who doesn’t really know how to play guitar in a traditional way.

Roxy Music was a massively important band to us. I was always playing at being a post-punk Brian Eno. He doesn’t consider himself a musician, and neither do I. Brian Eno always added something special to records—like the Talking Heads records and The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway [by Genesis].

Freestyle

After picking up the guitar, how soon was it before you started making your own music?

When I first started playing guitar, I began making music straight away. I never sat around learning how to play anyone else’s songs. It never interested me. I still don’t know how to play “Smoke on the Water.” I just wanted to make my own sounds and do my own thing. But I didn’t think about it at the time; I’d just pick a guitar up, start playing, and things would pop out.

There are a lot of tricks guitarists do that I can’t—blues licks that sound like certain people. I can’t do any of that stuff, and I don’t try learning any of it either. I’m really not interested in that, because there are so many other people doing it better.

Why would I need to do that? What’s the point? I mean, an artist doesn’t start trying to paint the Mona Lisa again, do they? Well, unless they’re taking the piss, like putting a moustache on it, like Marcel Duchamp did.

"When I first started playing guitar, I began making music straight away. I never sat around learning how to play anyone else’s songs."

Studio Practice

Do you have a practice routine?

I don’t sit around playing guitar, really. Maybe I should. I just like combining sounds and seeing where it goes. I hardly ever start with a preconceived idea. The ideas come as I go along. It’s trial and error. I hardly ever play, unless I’m recording or we have a gig and I need to remind myself of all the parts. Luckily, I remember most of them!

To me, guitars and music gear are just tools. My house is full of guitars. It’s ridiculous, but I keep storing them. I have a small studio, where I use Logic Pro to record.

How does this improvisational approach feed into your recording process?

A lot of the things I do are first takes that somebody might tell me about afterwards and say, “That thing you did then was good.” A lot of the time, the rhythm section would be going, and I’d try different takes and improvise to see what happens.

Often, the first thing you do is the best thing. Back in the day, using tape, you couldn’t edit as easily as you can now, so you had to commit.

Minimalism

Many of your standout guitar parts are deceptively minimal—what is it about simplicity and repetition that hits so hard?

It’s like an insistent thing. It gets more and more intense with repetition. I don’t know why, but it does. Playing loads of twiddly notes might be clever, but it can leave you cold.

I think some of the best ever guitar recordings were simple, like “Wichita Lineman” by Glenn Campbell, for one. Or the beginning of The Rolling Stones’ “Gimme Shelter.” As soon as you hear that track, it feels like the best thing going.

"It felt like all these creative possibilities were opening up for us."

Speed of Sound

In what ways did your experimental approach show up on the first Echo & the Bunnymen recordings?

Our first single, “The Pictures on My Wall” [released in 1979], was done on an eight-track. We sped up the tape and recorded a drum hit, so when it went back to normal speed, it was slowed and pitched down to get that big, boomy sound.

At the time, it felt like all these creative possibilities were opening up for us, like reversing the tape and chopping bits out and moving them. We were cutting two-inch tapes with razor blades. All this stuff was fascinating to me.

For the Record

In what ways did that creative mindset shape the recording of your first album, Crocodiles?

When we went into Rockfield Studios to work on Crocodiles, the engineer, Hugh Jones, introduced a lot of studio techniques that we’d never heard about. He really opened our eyes, and it blew our minds what was possible.

He’d do things like placing a microphone inside a piano or putting a guitar amp down one end of a corridor with a mic at the other end to capture the natural reverb.

"The engineer Hugh Jones introduced a lot of studio techniques that we’d never heard about. He really opened our eyes, and it blew our minds."

We got all kinds of unusual textures. He showed us a Leslie cabinet and what it did. I later used a Leslie on “Silver” [from Ocean Rain]. Hugh worked with us on the second Echo & the Bunnymen album, Heaven Up Here.

Heaven Up Here was also recorded at Rockfield—how did you continue to explore new sounds and techniques?

Hugh got this fella in [Les Penning] who was like the top recorder player in the country. Y’know, that thing you played in school? We thought, “The recorder! Who the hell has that on a record?” But it sounded really cool. You can hear it on “All My Colours.”

"We recorded a dredger and put it at the beginning of 'With a Hip.' The maddest thing is, it sounds like Mac’s voice saying, 'Good' and 'Crap.'"

Bill Butt, our lighting engineer from Bristol, had an Austin Champ—a military jeep with a large Rolls-Royce engine. We drove from Rockfield Studios down to Bristol Docks and took a Nagra tape recorder with us to record industrial noises.

Nagra recorders were professional bits of kit used in the film industry, and Bill was able to get hold of one through his contacts. We recorded a dredger and put it at the beginning of “With a Hip.” The maddest thing is, it sounds like Mac’s voice saying, “Good” and “Crap.”

Poetic Rhythm

Many Echo & the Bunnymen tracks feature unusual sounds and rhythms—can you share any standout studio moments?

At one point, we were sitting in a circle, recording a clapping rhythm that sounded really good. Another time, we used a slit drum—a plywood box with slits, which you hit in different places. Our drummer, Pete [de Freitas], used it to record a weird percussion thing on “My White Devil” [from Porcupine].

"'The Killing Moon' intro was just me checking to see if I was in tune and could hear myself through the headphones."

Crescent Moon

“The Killing Moon” is one of your most celebrated tracks—can you share how it came together in the studio?

We recorded “The Killing Moon” in Bath at Crescent Studios. The owner, David Lord, was helping produce us. David was the one who put the guitar intro to “The Killing Moon” together—the part that repeats right at the beginning of the song.

We were just tuning up and getting ready to do a take, but he already had the tape rolling. That intro was just me checking to see if I was in tune and could hear myself through the headphones.

We went for a curry around the corner, and by the time we came back, David had found this little guitar thing, put it on a quarter-inch tape, flew it into the beginning of the song on the master tape, and repeated it. It was like sampling. We all thought it was great. We loved it.

I’ve never figured out that intro part. I didn’t plan it, and I couldn’t remember doing it. It was totally on the fly, so I then had to learn a version to perform live. But to this day, I still don’t think I do it the proper way. The way I play it live is not how it is on the record.

"I’ve never figured out 'The Killing Moon' intro part. I still don’t think I do it the proper way. The way I play it live is not how it is on the record."

Moon Landing

The solo on “The Killing Moon” was just my Vox 12-string miked up without an amp. That’s why it’s got that weird sound. And that part with the vibrato arm drop [last verse line/chorus end] was recorded with a shitload of reverb, so it sounds dead eerie.

I used an autoharp with a contact mic for the choruses, tuned to those three chords: G major, C minor, and E minor. We also turned the tape over and added reverb to get a backwards swell effect before the autoharp chords. I use an autoharp with a pickup to play “The Killing Moon” live now.

I loved using tape for reverse guitar. We’d flip it over, mark it on the back with a chinograph pencil, then someone would shout “Now!” before playing some guitar in the same key. It was always an amazing surprise what you got. I think reverse guitar using tape sounds better. You can do it on a computer, but it’s not the same.

"I loved using tape for reverse guitar.

I think reverse guitar using tape sounds better. You can do it on a computer, but it’s not the same."

Moon Phases

How were the drums on “The Killing Moon” recorded?

Pete played the drums with sticks at Crescent Studios, but he’d started using brushes occasionally, which Mac really liked. We mixed “The Killing Moon” at Amazon Studios in Kirkby, near Liverpool, and Pete replaced his parts using brushes.

It was a risk doing that on a 24-track because we had to rub off all the original drums. But Pete did it in one take with just the other instruments to listen to.

Usually, it’s the other round; everyone else plays along to the drums. I was really worried at the time and didn’t think it was necessary. It could’ve easily not worked or sounded weird. But, looking back, I think it did add something special. So, I was wrong on that one.

Parlor Guitar

In the very early days, Echo & the Bunnymen didn’t have a drummer—how did you write and record before Pete de Freitas joined?

Yeah, it was only Mac and me to begin with, dicking around with a couple of guitars at my house in Melling [Merseyside] in my dad’s back parlor. We used to chug away for hours with a drum machine and record it all on tape using a crappy mic and a Bang & Olufsen tape recorder I’d bought off my mate.

"The drum machine helped us get tight rhythmically. Mac’s great at rhythm guitar. We’d just chug away for hours."

The drum machine helped us get tight rhythmically. Mac’s great at rhythm guitar. We thought we were The Velvet Underground, and we’d just chug away for hours. I’d play some notes and, now and then, Mac would say, “Oh, that’s good.” We were actually more into the Velvets than the punk stuff. We both loved Bowie and Lou Reed, and I was really into the Doors.

Sliding Doors

Tell us about recording “People Are Strange” with the Doors’ keyboardist, Ray Manzarek.

We did a cover of “People Are Strange” for The Lost Boys soundtrack. Ray Manzarek produced and played keys on that recording, and he also played keys on a song of ours called “Bedbugs and Ballyhoo.” I love the Doors, but, as I said, I didn’t sit around learning their songs. Our keyboard player, Jake Drake-Brockman, showed us how to play it.

I was obsessed with the Doors and started buying all their records after I heard them. The first Doors record I had was Strange Days, and I loved it. It’s kind of spooky.

Jim Morrison did this thing where he sings, but there’s a whispering vocal as well with echo and reverb going behind what he’s singing. I loved all the fairground-y organ, too. Like on “You’re Lost Little Girl.”

"We played our first gig at Eric’s on November 15, 1978. It was so loose that the whole thing could easily not have existed by the following week."

Stage Setting

How did the first Echo & the Bunnymen gig come about?

Julian Cope and The Teardrop Explodes were throwing a party on a Wednesday night at Eric’s club in Liverpool for the teacher training college he was going to—C.F. Mott in Prescot. This was when Paul Simpson was still in Julian’s band [Simpson departed in spring, 1979].

We were all punks, but not like London punks—more old suits than chains, whips, zips, and all that shit. We were into stuff like The Fall, Subway Sect, Pere Ubu, Talking Heads, and Gang of Four. We were all mates, and Julian knew that Mac and I had been doing stuff together, so he said, “You’re in a band; why don’t you support us?” And we just went, “Yeah, okay.”

We played our first gig at Eric’s on November 15, 1978. Our first song became “Monkeys.” Mac’s lyrics were about evolution. He had a little book he was reading lyrics from.

We hadn’t actually heard him sing until he did the gig. We were just told, “Mac can sing,” and that was enough. It was so loose that the whole thing could easily not have existed by the following week.

"Les Pattinson got his bass just two days before our first gig. He just did it. Once you’re on a stage, it becomes reality, and there’s no turning back."

Bass Jumping

How did you get Les Pattinson on board to play bass?

Just after we agreed to support Julian Cope and The Teardrop Explodes, someone said, “You’re going to need a bass player.” Les happened to be there in Eric’s with Paul Simpson (we all went to school together), and he said, “I’ll play bass.” I just went, “Yeah, okay,” even though he didn’t even own a bass.

Luckily, there was a lad there called Robbie who told us he had a bass and amp for sale for thirty quid, so we went to his house in Boole [Merseyside], and Les bought it. It was a Grant and had three strings on it.

We quickly arranged a rehearsal for the following Monday, but Mac never showed up, so it was just Les and me. We rehearsed a little riff I had, with the drum machine ticking away in the background.

Les got his bass just two days before our first gig. He just did it. But he’s Mister Solid. When you’re only talking about it, it doesn’t mean anything. But when you actually do it, it becomes a thing. Once you’re on a stage, it becomes reality, and there’s no turning back.

"On the day of our first gig, Julian Cope introduced us on stage. He said, 'Echo & the Bunnymen,' and I thought, 'Where’s he got that from? There’s no chance I’m going to be called that.'"

Applaud to the Echo

What’s the story behind the name Echo & the Bunnymen?

On the day of the gig at Eric’s, Julian introduced us on stage. He said, “Echo & the Bunnymen,” and I thought, “Where’s he got that from? There’s no chance I’m going to be called that.” He’d seen it in a list of names that Mac’s flatmate had written and just picked that one.

It wasn’t even decided that we would be called Echo & the Bunnymen going forward, but after the gig at Eric’s, it stuck. I liked “Bunnymen,” but not the “Echo & the” bit.

What was the reaction to the first Echo & the Bunnymen gig?

Jayne Casey [Big in Japan vocalist] was there. She was the queen of Eric’s. She was mates with Holly Johnson and Paul Rutherford [of Frankie Goes to Hollywood], who we looked up to as the uber-punks. Holly used to wear Vivienne Westwood bondage kecks while we were going around the charity shops.

Jayne was like the Siouxsie Sioux of Liverpool. She came into the dressing room and told us, “That was amazing!” I was taken aback because I felt like they were out of our reach. To get her approval meant a lot to me.

"Echo & the Bunnymen was just a surrealist combination of words."

But there were also a few snide comments. Loads of local bands were there watching that night, and you could tell some of them were thinking, “These guys can’t even play.” I was using one string, and my playing was very minimal.

I remember Les glaring at one of these lads who was laughing at us behind his hands. But there was no more laughing when it kicked off.

Echo Chamber

There’s a rumor that “Echo” is the name of the drum machine you used to play live and record—is that true?

No. As the years went on, people kept asking, “Who’s Echo?” People thought Mac was Echo, and the rest of the band were the Bunnymen. I wasn’t happy about it, and neither was Mac. He didn’t want to be called Echo. Mac made up the story of Echo being the drum machine on the spot when a journalist asked him who Echo was.

That explanation stuck, and we carried it on, but Echo wasn’t anything—Echo & the Bunnymen was just a surrealist combination of words. Mac’s flatmate had loads of names on that list, like Glycerol and the Fan Extractors. Mona Lisa and the Grease Guns was another. There was one I quite liked: The Daz Men.

"We sampled the TR-66 and experimented with it in various ways over the years. It’s a cool thing."

Deus Ex Machina

When did you start using the Roland TR-66 Rhythm Arranger drum machine?

Probably around the time of Heaven Up Here. I was always into experimental music, and I loved Kraftwerk and those Brian Eno albums with drum machines on, Before and After Science and Another Green World.

The first drum machine we had was a Korg Mini Pops Junior. I sprayed it red, then fluorescent green. It was stolen from our rehearsal place, and we never saw it again.

There were two Roland TR-66 drum machines floating around, and I think one of them belonged to The Teardrop Explodes. We sampled the TR-66 and experimented with it in various ways over the years. It’s a cool thing. It sounds better than the Korg Mini Pops Junior, and it’s got a few more options.

"I used to start and stop the drum machine with a footswitch... I had headphones connected to the hi-fi amp, so I could hear it and count everyone in."

The TR-66 is pretty basic—not like a TR-808 Rhythm Composer, which really changed the game. I also had a Roland TR-606 Drumatix, but it got stolen. I wanted to get the TB-303 Bass Line when that came out in the early ’80s, though I couldn’t afford it at the time.

On the Beat

How did you control the drum machine on stage?

I had to change the tempo with a dial for different songs, and I used to start and stop it with a footswitch. I connected the drum machine to a Pioneer hi-fi amplifier, and from there it went to the PA.

I had headphones connected to the hi-fi amp, so I could hear it and count everyone in. The footswitch was placed between the amplifier and the PA, and when I stepped on it, it released the signal.

I’ve always done stuff separate from the band, mainly for fun. I like things that sound filmic."

Flying Solo

What inspires you to explore new directions in your solo work?

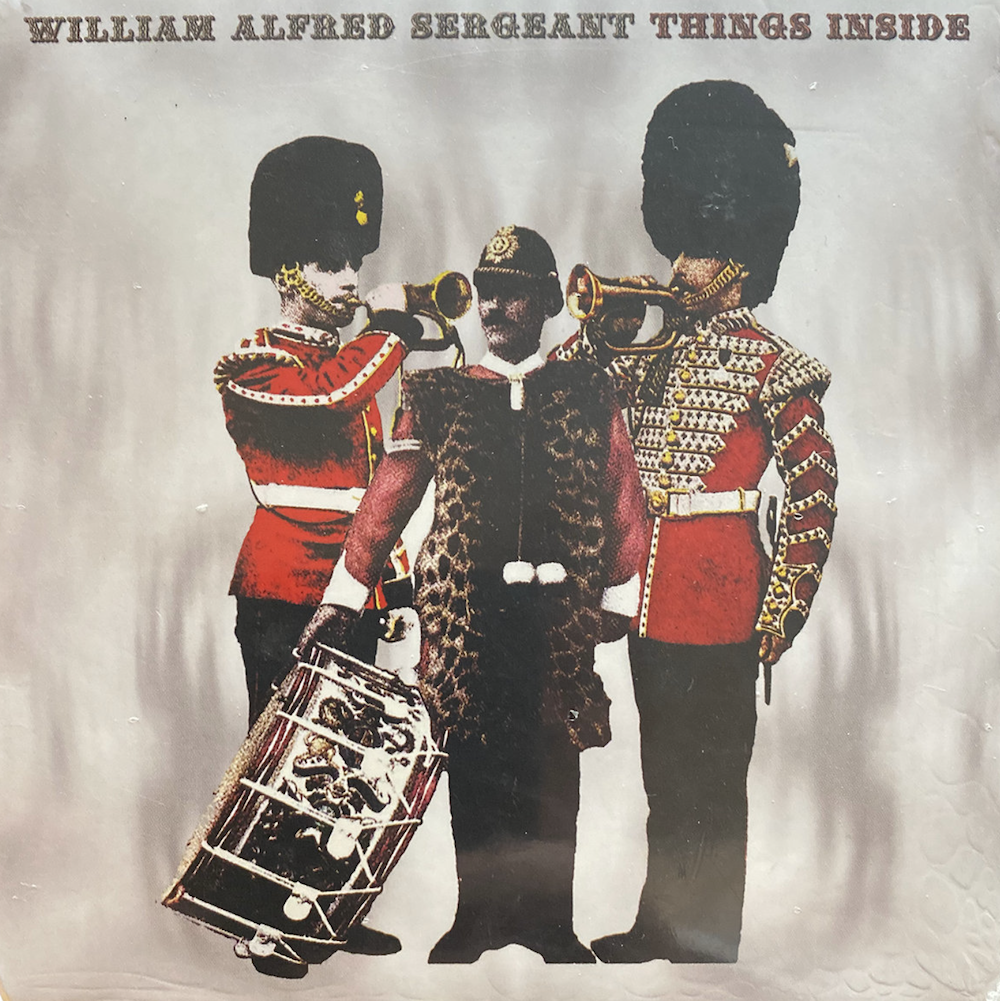

I’ve always done stuff separate from the band, mainly for fun. I did a solo acoustic instrumental album called Things Inside [released in 2012] with our regular engineer, Andrea Wright. She’s brilliant. She works with The Brian Jonestown Massacre a lot.

I borrowed all the acoustic instruments because I’d never made a record like that before. I used a couple of nice Martins and a ukulele, along with some other bits and bobs.

We went into a studio in Liverpool, and I just started playing while Andrea recorded it all on Pro Tools. We picked out all the good bits and made an entire album. There were no ideas until the ideas appeared. I think it’s a good approach because you’re not trying to sound like anyone else.

Things Inside sounds eerie. It reminds me of The Wicker Man. I’ve always wanted to get into soundtrack stuff. I like things that sound filmic. I’ve done the odd thing, but it’s difficult work to get into.

"Glide is an electronic project of mine.

The concept of Glide was to create an electronic record that doesn’t sound like it was done on a computer."

Glide Path

What was the creative vision behind Glide, and how did you bring it to life?

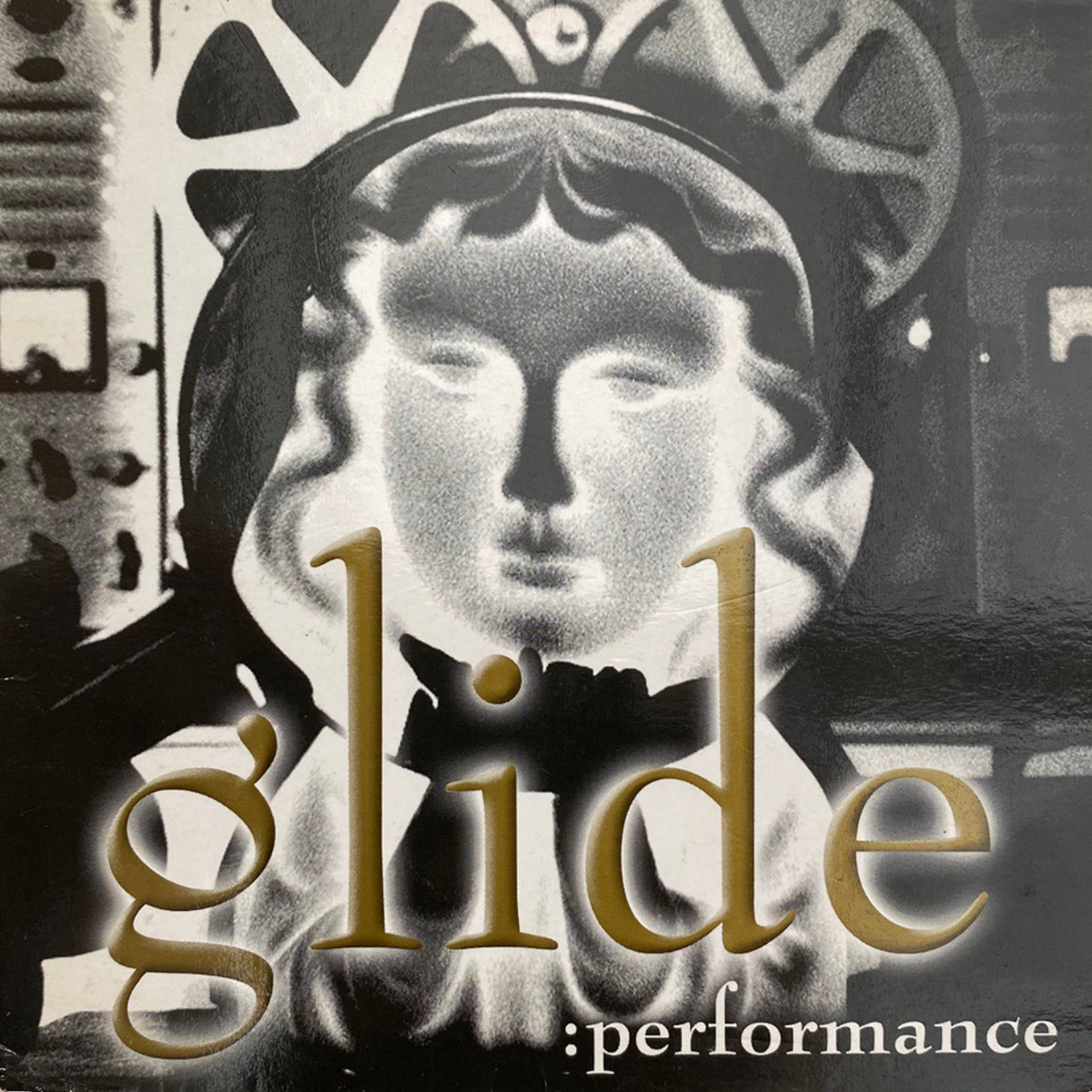

Glide is an electronic project of mine, inspired by Tangerine Dream. It’s on the periphery of the rave thing. It’s all recorded on a computer using lots of sequencing and arpeggiators.

The concept of Glide was to create an electronic record that doesn’t sound like it was done on a computer. Some tracks were reamped using pedals, and I did bits of guitar—dreamy, Pink Floyd-style stuff.

I like electronic music like Aphex Twin and ambient acid-style stuff, like Dreamfish with Mixmaster Morris and Pete Namlook. Back in the day, I used to go and see The Orb. More recently, I’ve been listening to Steve Davis’s electronic group, The Utopia Strong. I got a record of theirs the other day, and it’s brilliant.

I also like The Advisory Circle, particularly the album Mind How You Go. It’s kind of like the ’80s science television show piss-take Look Around You.

"There’s an Echo & the Bunnymen record in the pipeline, and we have a UK tour coming up in 2026."

New Horizons

What’s on the horizon for Echo & the Bunnymen?

There’s a record in the pipeline, and we have a UK tour coming up in March and April 2026. Then we’re going over to America in May and June for five or six weeks. I’m looking forward to it. There are some European dates too.

I really like America. After a while, I met people who were just as sarky as us. I really like it now, and I miss it when we don’t go there. We’ve been going regularly since 1981.

Some of the first US gigs we did were at the Whisky a Go Go in Los Angeles, which blew my mind because I’m such a massive Doors fan.