Guitarist Adrian Utley is renowned as a member of the influential Bristol trio Portishead. Meanwhile, bassist Jim Barr is widely recognized for his long-standing role with the group, having been a key member of their live band from the beginning. The prolific musicians also worked together on a range of projects before and after Portishead’s inception. Their latest collaboration, 137, is a compelling journey into free improvisation that challenges conventional notions of musical expression.

Ferocity and Fragility

The all-star experimental jazz ensemble 137 brings Utley and Barr together with drummer Seb Rochford and saxophonist/flutist Larry Stabbins for a dynamic and multifaceted musical venture. Though each musician is a master of their craft, they remain humble and driven in their pursuit of artistic growth. As Utley sees it: “Every day is a school day.”

137’s debut album, Strangeness Oscillation, appeared earlier this year and is described as “a collection of completely improvised recordings that captures the ferocity and fragility of these four players’ unique combined voice.” “Ferocity and fragility” may appear contradictory, but 137 embraces duality with certain unpredictability, momentary permanence, and calculated chaos. “I feel like we live in times of chaos, so I don’t want to restrict and organize; I’m going with the chaos,” Utley explains.

We visited Barr’s Bristol-based recording facility, J & J Studio, to explore the making of 137’s astounding new release. Here, the quartet tracked Strangeness Oscillation with the help of Utley’s longtime studio ally, Tim Allen (Bat for Lashes, Hannah Peel, Anna Calvi).

An Experiment in Free Thought

What is 137?

Adrian Utley: 137 is a foray into free improvising—an experiment in free thought. It’s an interesting learning curve, and playing with everybody is great. Over the years, I’ve worked on many things with Seb, Jim, and Larry. We’re kindred spirits. 137 is unlike a lot of other things I’ve done previously because I know that what I do in the moment is it. And I’ve become a much more confident player because of that.

How did you approach recording Strangeness Oscillation?

Jim Barr: Tim Allen approached it in an uncomplicated way. For example, drums were recorded using mics just on the kick and snare, plus a couple of overheads. It wasn’t a fussy setup, but we used nice mics. In terms of mixing, we realized early on that it sounded much better dry than using lots of reverb. Apart from wind instruments, everything is bone dry. We just brightened it up and pushed it a bit.

AU: We panned the sax and guitar a bit wider to make sure there was enough space and things didn’t get piled on top of each other. It stays like that throughout the whole album. Also, we wanted it to sound like it was coming out of a 1970s WEM PA system with no subs.

"137 is a foray into free improvising—an experiment in free thought."

Adrian Utley

All eight tracks on Strangeness Oscillation are improvised compositions. How does this translate live?

JB: It’s weird to go and improvise something live that you completely made up on the spot earlier. How do you go back to it without trying to recreate it? How do you recreate the record’s atmosphere without just playing it again? It’s a paradox. We’re trying not to think when improvising with an audience. If you try to make it go somewhere, it loses its essence.

Recording is another thing because you do have to revisit it; you have to go back, work it out, and accept it somehow. When we were all sitting around listening to the recordings, we didn’t know if it was good or not at first. At some point, we just all agreed it was great. I’ve been through that process before with my other band, Get the Blessing. It’s about acceptance. You absolutely can record something you’ve never played before, and it can be good if you allow that to happen. Considering the players involved in 137, why wouldn’t we want to?

AU: Jim did a lot of chopping up, and we overdubbed a couple of things.

JB: It was just a process of going through the recordings and deciding what was good and what wasn’t. Weirdly, the stuff on the album appears more or less in the order we recorded it. Apart from the fact that we chopped “First Idea” in half and bookended the album with it.

"It’s not gonna compete with Taylor Swift, but I’m digging it."

Adrian Utley

Adventure and a Journey

Why do you like to use first takes?

AU: First takes are usually more vibey. I’d rather it was a first take as they’re often the best if you can concentrate. I’m super concentrated the first time, so I’ll go for the first take and repair anything I didn’t get right. When I recorded with Jim for Get the Blessing, almost everything was done in the first take, too.

Has this creative process taught you anything?

AU: Yes, definitely. My whole musical life has been an adventure and a journey. 137 has taught me to be more confident starting from nothing aside from other musicians—a totally blank piece of paper. We don’t even have a preconceived key. When we play “First Idea” live, none of us know where the beginning of the bar is. Does it matter? Is it in 9/8? 11/16? 4/4? What does “the one” even mean? It’s not gonna compete with Taylor Swift, but I’m digging it.

"It’s about acceptance. You absolutely can record something you’ve never played before, and it can be good if you allow that to happen."

JIm Barr

JB: I try to hide the pattern—not in a self-conscious way, but just to prevent it from getting stuck and becoming rigid.

AU: You know the ostinato at the beginning of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells—the part that was used for The Exorcist soundtrack? The bars vary in length, so it slips all the time, and your brain is always surprised by it. If it was always in 4/4, it might be a bit boring. That’s kind of what we’re trying to do.

JB: It makes your brain feel a bit itchy. Having said that, some tracks are very loopy, like “Two Base Flute” and “Bass Clarinet One.” They’re not super simplistic rhythmically but there’s a definite pattern that keeps going and going. That hypnotic element is another thing altogether. It’s like two ends of the spectrum. One thing says, “You can’t go to sleep,” and the other says, “Go to sleep.” The hypnotic synth sequence in “Bass Clarinet One” was an overdub. We just ran it and didn’t change a thing.

AU: I had the Herbie Hancock track “Rain Dance” in mind, so I brought an ARP 2600 in.

"The first thing you hear on the album is literally the first thing we played together. That's why it's called 'First Idea.'"

JIm Barr

JB: For “Two Base Flute,” Ade suggested we do something with two basses. We rebuilt that because it was cool, but there wasn’t enough of it. We wanted more, so we used a big chunk of something Seb had done and looped it around three or four times. After that, we put the basses back on top and put what Larry had done back in. That’s one of the things about improvisation: sometimes, it moves on too quickly, and you wish you could have kept it going a bit longer.

A Naïve Approach

How did you kick off the Strangeness Oscillation sessions?

JB: The first thing you hear on the album is literally the first thing we played together. That’s why it’s called “First Idea.” Everything was recorded here at J & J Studio in Bristol. We were all standing in the same room, apart from Larry, who played in a booth for a bit. He’s a very loud saxophone player.

AU: He’s the loudest saxophone player I’ve ever played with. That’s how he gets his sound.

“Drum and Sax” might be a good example of that.

JB: “Drum and Sax” was a drum solo with us making a supportive racket underneath. After a minute, Larry does his “fire in a pet shop” thing. It’s so brutal that I literally jumped off the sofa while listening to the test pressings.

AU: “Drum and Sax” was based on a set of notes that I’d pre-written. I used musical allegory, where I make words into notes. Not that I’m comparing myself to them, but Bach and Shostakovich had similar systems. Limitations can set you free.

"Limitations can set you free."

Adrian Utley

It’s reminiscent of Captain Beefheart’s “Hair Pie: Bake 1.”

JB: Somebody else told Larry that it reminded them of Trout Mask Replica, and he was really pleased with that. He was so happy they made that connection. Even though a lot of the Trout Mask Replica album was tightly arranged and well-rehearsed, it comes from the same place as 137. Don Van Vliet improvised using a piano, whistling, or his voice, and then John French transcribed it for the Magic Band. It’s a kind of naïve approach, but that’s what’s great about this kind of thing—stuff happens that wouldn’t happen otherwise.

We just launched ourselves into it and ended up playing notes that we wouldn’t have played if we had known what key it was in before we started. You make it fit. It starts to sound interesting if you play the wrong notes for long enough.

Did you prepare any compositions for the recordings?

AU: The premise of Strangeness Oscillation was that we would improvise all the way through. There was one thing—a simple set of notes—written out. That’s why it ended up being called “Ade’s Tune.” It was a little groove, a riff that I recorded on my iPhone and labeled “Tune for Larry,” followed by an idea called “Melody.” I put those two things together and wrote a little chart for Larry, but then Seb and Jim came up with a great groove. The thing with Seb is that you know he will come up with a rhythm you wouldn’t have ever thought of.

"The premise of Strangeness Oscillation was that we would improvise all the way through."

Adrian Utley

JB: “Ade’s Tune” was a seed that turned into something much bigger.

AU: I thought I’d come with a couple of small things prepared in case we zoned out and had nothing going on. As it happens, we went for the cake on the first day.

Adrian, your guitar of choice for 137 is a Fender Jazzmaster, which is unusual for jazz, ironically.

AU: It is, yeah. But they’re brilliant. For me, the Jazzmaster is a revelation. When I got my first one, everything changed. I had a Stratocaster when I was younger, but I’d wanted a Jazzmaster ever since working with John Parish. I recorded the whole album with a new Vox AC10 and my black 1962 Jazzmaster, apart from one track, “Trichotomy Book,” when I used my old Guild T-100D thinline strung with heavy flatwounds.

Modulation and the Massive Cycle

How are you using effects pedals with 137?

AU: I have a germanium Fuzz Face circuit that was transplanted into a different box, and I use the guitar volume control quite a bit to clean up the signal. I still love an old Tone Bender or Fuzz Face. I’ve also got a DD-3 Digital Delay on the pedalboard. I set it really fast and with the Feedback knob almost up full. I’ll hit a note and switch it on, and it sounds like a machine gun. I’ll switch it off on the beat before it goes into full feedback. I also like to use the DD-3 as slow as it can go with the feedback turned up, so you get an endless repeat you can play against. It’s like a massive cycle of riffs. I have an old Electro-Harmonix Deluxe Memory Man as well. I like the vibrato sounds you can get from that pedal.

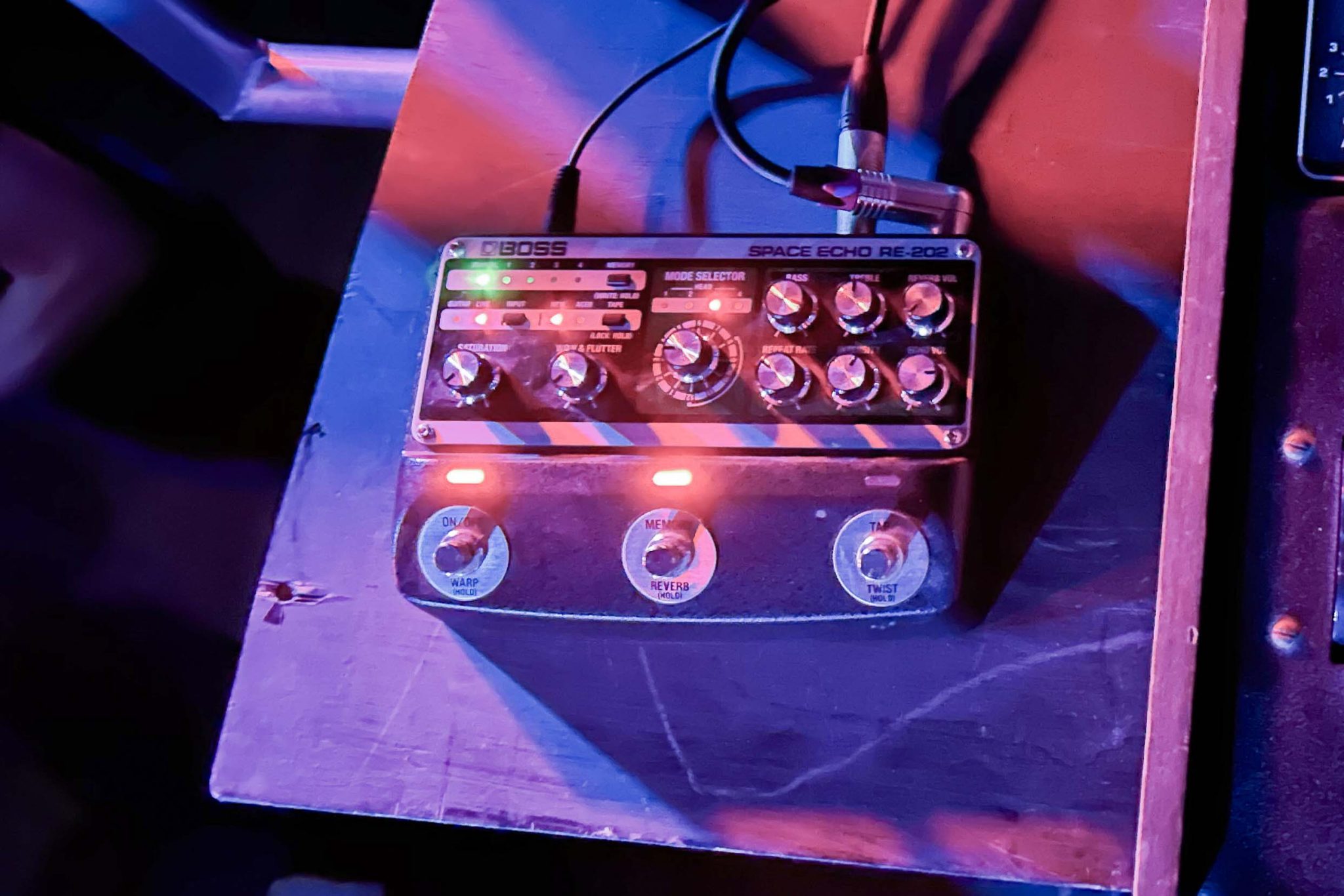

"The RE-202 Space Echo sounds just as good as the old original tape echo units."

Adrian Utley

The BOSS RV-5 Digital Reverb is one of my favorites. I bought it for the Spring mode initially but couldn’t stop using the Modulate mode once I discovered that. I’ve had it on Modulate consistently for years now. My live synths are going through the RE-202 Space Echo pedal, which sounds great. I love it. I’ve got an immaculate RE-201 Space Echo from Soundgas, but it’s not as reliable as the RE-202. The RE-202 Space Echo sounds just as good as the old original tape echo units. The technology is there now, I reckon.

What did your recording rig look like, Jim?

JB: It was an Ampeg V4B with a 2×10, plus my usual mix of pedals, including the BOSS FZ-2 Hyper Fuzz, OC-2 Octave, and the ubiquitous TU-3 Chromatic Tuner. The OC-2 is great because it yodels a bit, and you can’t make that sound any other way. I like the savage FZ-2 sound—that kind of sawtooth thing that works great with bass. What’s really cool about the Hyper Fuzz is that you can dial clear low-end in using the tone control. For bass, it’s the ideal balance between cutting fuzz and weightiness.

Have you ever used BOSS or Roland guitar amps?

JB: The Roland Jazz Chorus amps are brilliant. They’re very robust and seem to be able to take anything. I’ve got a Roland Cube amp, too. You can put anything into it; it sounds great—keyboards, guitar, bass, anything.

AU: Yeah, the Jazz Chorus amps are great. I gave Will Gregory a couple of Roland Cube amps for his Moog Ensemble. They’re really good. I took them on tour with Portishead to use as keyboard amps. I’ve kept hold of one, though.

"Larry disappeared for ten years. Years later, we got a phone call from Larry out of the blue saying, “I’m back! I’ve bought a saxophone."

Jim Barr

The Bristol Soup

Speaking of Portishead, there’s a rich history among the members of 137. How did your paths first cross?

JB: I met Larry through Adrian, and I met Adrian because I was trying to get guitar lessons from him back in the early ’90s. I can’t remember any lessons actually taking place, but we ended up doing some jazz gigs together, one of which was at Ashton Court with Larry. Adrian and I ended up doing quite a lot of jazz gigs, including with Clive Deamer, the Portishead drummer. Clive also plays in Get the Blessing.

AU: With Portishead, we had to get a live band together, and I was the only one who knew any musicians. Clive had already recorded drums on Dummy, and then I asked Jim and Johnny Baggott to join. That’s how the Portishead live thing happened. We’d been working together quite a lot before that. There was a sort of soup of Bristol musicians who always turned up on each other’s projects.

Tough Stuff

Tell us about your earlier work on Larry’s Stonephace project.

JB: We both worked on that; I played double bass, and Adrian played guitar. But then Larry suddenly disappeared! I called him up and asked him what was happening with the record we were making, and he told me he had enough and was selling all his saxophones. He then disappeared for ten years, having decided to sail around the world with his wife. Years later, we got a phone call from Larry out of the blue saying, “I’m back! I’ve bought a saxophone. When are we doing this album?”

"There was a big period of my life when I only played jazz guitar...After a while, I decided I didn’t want to play straight-ahead jazz."

Adrian Utley

AU: He’s a hardcore climber, too. We’re talking about crazy stuff like climbing up frozen waterfalls. He’s an interesting guy. He studied philosophy at Kings College London but is from Bristol originally. I first met Larry in the early ‘90s when I had a house band residency in Bath before Portishead started. There was a big period of my life when I only played jazz guitar. We were doing straight-ahead groove jazz, and every couple of weeks, we’d have guests, one of whom was Larry. I rang him up, thinking he’d never do it, but he did, and we’ve been mates ever since.

After a while, I decided I didn’t want to play straight-ahead jazz and got more into breakbeat stuff. I discovered A Tribe Called Quest, which led me into hip hop. Then I met Geoff Barrow. All the early Portishead stuff was straight out of my study of that kind of music.

When did you first play with Sebastian Rochford?

AU: I’m a big fan of Marc Ribot, whom Jim and I have both played with before. I played with Seb for the first time in London with Marc and Shahzad Ismaily. Lol Coxhill, the legendary saxophone player, was sitting right in front of me in the audience. He was a lifelong free improviser of enormous stature, and this was one of my earliest journeys into free improvisation. So, I felt a little intimidated, to say the least. That was the early days of me getting involved with this sort of thing, and I’m only just starting to feel a little freedom from myself.